Health Effects of Vegan Diets

Topic

- Iron

- Calcium

- Diet

- Food

- Zinc

- Diet

- Vegan

Issue Section

Health and nutritional status of vegetarians

INTRODUCTION:

According to a countrywide poll done by Harris Interactive in April 2006, 1.4 percent of the American population is vegan, meaning they don’t eat meat, fish, dairy, or eggs. Vegan diets are becoming increasingly popular among teenagers and young people, particularly ladies.

Many vegans’ nutritional decisions are based on environmental concerns, ethical concerns about animal welfare, the use of antibiotics and growth boosters in the production of animals, the threat of animal-borne diseases, and the health benefits of a plant-based diet. Furthermore, the possibility of dairy-related allergies and lactose intolerance has boosted the appeal of soy-based dairy alternatives.

So, how does a vegan diet affect their nutritional and health status? Are there any advantages or disadvantages to following a vegan diet compared to other vegetarians (e.g., lactoovovegetarians)? Is there any further benefit to eliminating dairy and eggs, or are there any potential risks?

The goal of this brief study is to outline the current understanding of the health impacts of vegan diets, identify nutritional problems or shortages, and offer some practical dietary suggestions for following a healthy vegan diet. Key et al. provide a useful review of the health impacts of vegetarian diets, concentrating on their European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition–Oxford (EPIC-Oxford) study as well as other large population studies.

HEALTH EFFECTS OF VEGAN DIETS

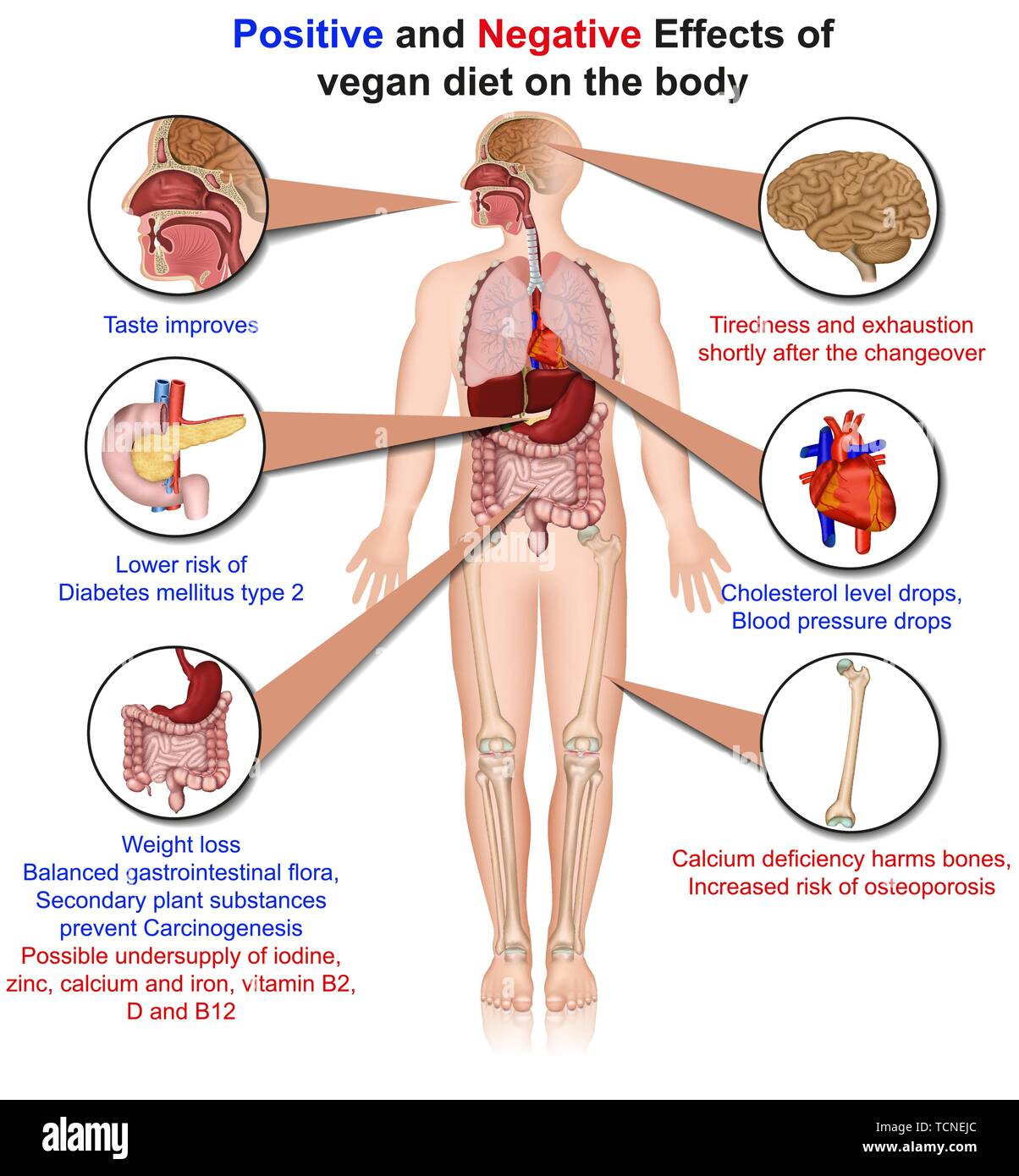

Vegan diets tend to be richer in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamins C and E, iron, and phytochemicals while being lower in calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain n-3 (omega-3) fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B-12. Vegetarians have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, type 2 diabetes, and some malignancies in general.

A vegan diet appears to be beneficial for enhancing preventive minerals and phytochemicals while reducing dietary variables linked to a variety of chronic illnesses. Different plant dietary groups were graded according to their metabolic-epidemiologic evidence for affecting chronic illness reduction in a recent report.

Cancer risk reduction associated with a high intake of fruits and vegetables was assessed as probable or possible, risk of CVD reduction as convincing, and lower risk of osteoporosis was assessed as probable or possible, according to the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization (WHO/FAO) evidence criteria.

The evidence supporting a risk-lowering impact of whole grains was rated as likely in the case of colorectal cancer and probable in the case of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Supporting CVD, the evidence for a risk-lowering impact of nuts was rated as likely.

Cardiovascular disease

In a summary of the published data, Fraser stated that vegans are slimmer, have lower total and LDL cholesterol, and have somewhat lower blood pressure than other vegetarians. This is true not just for whites; Toohey et al found that African American vegans’ blood lipids and body mass index (in kg/m2) were considerably lower than lactoovovegetarians’.

Similarly, vegetarians have lower plasma lipids than their omnivorous counterparts in Latin America, with vegans having the lowest. Vegans had 32% lower total and 44% lower LDL cholesterol in their blood than omnivores, according to the study. Because obesity is a key risk factor for CVD, vegans’ significantly lower mean BMI may be an essential preventive factor in lowering blood lipids and lowering heart disease risk.

In comparison to omnivores, vegans consume significantly more fruits and vegetables. Higher consumption of fiber-rich fruits and vegetables, as well as folic acid, antioxidants, and phytochemicals, is linked to lower blood cholesterol levels a decreased risk of stroke, and a lower risk of death from stroke and ischemic heart disease. Vegans also consume more whole grains, soy, and nuts which all have strong cardioprotective properties

Cancer

According to the Adventist Health Study, nonvegetarians had a significantly higher risk of colorectal and prostate cancer than vegetarians. A vegetarian diet has several cancer-fighting nutrients. Obesity is also a key factor, increasing the risk of cancer in a variety of ways. Vegans’ mean BMI is significantly lower than nonvegetarians’, suggesting that it may be an important preventive factor in lowering cancer risk.

Vegans consume significantly more legumes, fruits and vegetables in general, tomatoes, allium vegetables, fiber, and vitamin C than omnivores. All of the foods and nutrients have anti-cancer properties. Fruit and vegetables have been shown to protect against cancers of the lung, mouth, esophagus, and stomach, as well as several other sites to a lesser extent, whereas frequent consumption of legumes protects against stomach and prostate cancer.

Furthermore, fiber, vitamin C, carotenoids, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals in the diet have been demonstrated to protect against cancer, with allium vegetables protecting against stomach cancer and garlic protecting against colon cancer. Tomatoes, for example, are high in lycopene, which is believed to protect against prostate cancer.

Fruits and vegetables are known to have a diverse variety of phytochemicals with strong antioxidant and antiproliferative properties, as well as additive and synergistic effects. Phytochemicals halt the progression of cancer by interfering with a variety of cellular processes.

Cell proliferation is inhibited, DNA adduct formation is inhibited, phase 1 enzymes are inhibited, signal transduction pathways and oncogene expression are inhibited, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis are induced, phase 2 enzymes are induced, nuclear factor-B activation is blocked, and angiogenesis is inhibited.

Interestingly, population studies haven’t found more pronounced differences in cancer incidence or mortality rates between vegetarians and nonvegetarians, given the extensive range of beneficial phytochemicals in the vegetarian diet. The phytochemicals’ bioavailability, which is influenced by a variety of factors including food preparation procedures, could be a major deciding factor. However, emerging research reveals that a deficiency in vitamin D, which is common among vegans is linked to an increased risk of cancer.

Vegans’ protein sources, whether avoided or consumed, have clear health implications. Consumption of red and processed meat is regularly linked to an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Those in the top quintile of red meat consumption had higher odds of esophageal, liver, colorectal, and lung cancers, ranging from 20% to 60%, than those in the lowest quintile.

Furthermore, the use of eggs has lately been linked to an increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Vegans consume more legumes than omnivores, even though they forego red meat and eggs entirely. In the Adventist Health Study, this protein source was found to be connected with a lower incidence of colon cancer.

According to new research, eating legumes is linked to a moderate reduction in the incidence of prostate cancer. Vegans consume significantly more tofu and other soy products than omnivores in Western civilization. Consumption of isoflavone-rich soy products during childhood and adolescence protects women from breast cancer later in life, whereas a high childhood dairy diet has been linked to an increased risk of colon cancer later in life.

Vegans’ cancer risk may be influenced by their consumption of soy beverages rather than dairy beverages. The Adventist Health Study found that vegetarians who consumed soy milk were less likely to develop prostate cancer, but dairy consumption was linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer in previous studies.

Because there are numerous unsolved concerns about how food and cancer are linked, further research is needed to investigate the link between plant-based diets and cancer risk. Epidemiologic research has yet to produce solid evidence that a vegan diet offers considerable cancer prevention. Even though plant meals contain a variety of chemopreventive compounds, the majority of study data comes from cellular biochemical studies.

Bone health

There are no differences in bone mineral density (BMD) between omnivores and lactoovovegetarians, according to cross-sectional and longitudinal population-based research published in the last two decades. More recent research with postmenopausal Asian women found that long-term vegetarians had significantly decreased spine or hip BMD.

Protein and calcium intake were low in Asian women who were vegetarian for religious reasons. Bone loss and fractures in the hip and spine have been linked to insufficient protein and calcium intake in the elderly. For vegans, getting enough calcium may be a challenge. Vegans frequently fall short of the necessary daily calcium intake, even though lactoovovegetarians ingest acceptable amounts.

The EPIC-Oxford study found that vegetarians have a similar incidence of bone fractures as omnivores. Vegans tend to have a higher risk of bone fracture as a result of a lower average calcium intake. There was no difference in the fracture rates of vegans who took more than 525 mg of calcium per day compared to omnivores.

Protein and calcium intake aren’t the only factors that affect bone health. Nutrients like vitamin D, vitamin K, potassium, and magnesium, as well as foods like soy fruits, and vegetables, have been proven to influence bone health. Vegan diets are high in a number of these essential nutrients.

Maintaining a healthy acid-base balance is essential for bone health. Because bone calcium is used to buffer pH drops, a drop in extracellular pH induces bone resorption. As a result, an acid-forming diet raises urine calcium excretion.

However, a vegan diet rich in fruits and vegetables has a good influence on the calcium economy and bone metabolism markers in both men and women. Fruit and vegetables have a high potassium and magnesium content, which produces alkaline ash that prevents bone resorption. Premenopausal women with higher potassium intake have higher BMD in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.

Undercarboxylated osteocalcin, a sensitive marker of vitamin K status, is used as a predictor of BMD and a predictor of hip fracture in the blood. Two large prospective cohort studies have found a link between vitamin K use and the incidence of hip fracture. Middle-aged women who consumed the most vitamin K had the lowest risk of hip fracture in the Nurses’ Health Study.

When compared to 1 serving/week of green leafy vegetables (the main vitamin K source), the risk of hip fracture was reduced by 45 percent. Elderly men and women in the highest quartile of vitamin K intake had a 65 percent lower risk of hip fracture than those in the lowest quartile, according to the Framingham Heart Study.

In addition to the high consumption of fruits and vegetables, vegans consume a lot of tofu and other soy products. It’s been hypothesized that soy isoflavones can help postmenopausal women’s bone health. Soy isoflavones demonstrated a significant benefit to menopausal women’s spine BMD in a meta-analysis of ten randomized controlled studies.

In a separate meta-analysis, soy isoflavones were found to dramatically reduce bone resorption and increase bone growth when compared to a placebo. Increases in BMD of both the lumbar spine and the femoral neck were significantly larger with the soy isoflavone genistein than with placebo in a 24-month randomized clinical trial involving osteopenic postmenopausal women.

Vegans’ bone health is unlikely to be a concern as long as their calcium and vitamin D intake is appropriate, as their diet offers an abundance of other bone-health-promoting nutrients. More research is needed, however, to provide more conclusive data on vegans’ bone health.

POTENTIAL NUTRITIONAL SHORTFALLS

To acquire a nutritionally balanced diet, the consumer must first have a thorough understanding of what constitutes such a diet. Second, accessibility, or the availability of particular foods and those fortified with vital nutrients that are otherwise absent in the diet, is critical. Because different countries have varied fortification laws, this accessibility will vary drastically based on the geographic region of the world.

The next section discusses the nutrients that should be avoided in a vegan diet. The issue of insufficient calcium was already mentioned in the bone health section. To acquire a nutritionally balanced diet, the consumer must first have a thorough understanding of what constitutes such a diet.

Second, accessibility, or the availability of particular foods and those fortified with vital nutrients that are otherwise absent in the diet, is critical. Because different countries have varied fortification laws, this accessibility will vary drastically based on the geographic region of the world. The next section discusses the nutrients that should be avoided in a vegan diet. The issue of insufficient calcium was already mentioned in the bone health section.

N-3 Polyunsaturated fat

Long-chain n-3 fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n-3), are crucial for cardiovascular health as well as eye and brain functions and are often lacking in diets that do not include fish, eggs, or sea vegetables (seaweeds). The plant-based n-3 fatty acid -linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3n-3) can be converted to EPA and DHA, but only to a limited extent.

Vegetarians, particularly vegans, tend to have lower blood concentrations of EPA and DHA than nonvegetarians. Vegans, on the other hand, can get DHA from microalgae supplements and foods fortified with the nutrient. EPA, on the other hand, can be obtained through the body’s retro conversion of DHA. Brown algae (kelp) oil has also been discovered to be a good source of EPA.

The revised Dietary Reference Intakes prescribe 1.6 and 1.1 grams of ALA per day for men and women, respectively, accounting for around 1% of daily calories. EPA plus DHA intake in the United States is currently just 0.1–0.2 g/d, with DHA intake being 2–3 times that of EPA. Vegans should be able to easily meet their n-3 fatty acid requirements by including ALA-rich foods and DHA-fortified meals and supplements in their diet regularly.

DHA supplements, on the other hand, should be used with caution. They can lower plasma triacylglycerol, but they can also raise total and LDL cholesterol, produce extremely long bleeding times, and impair immunological responses.

Vitamin D

Vegans had the lowest mean vitamin D consumption (0.88 g/d) in the EPIC-Oxford trial, which was one-fourth that of omnivores. Vitamin D levels in vegans are determined by both sun exposure and the consumption of vitamin D-fortified foods. Those who live in places where fortified foods are not available would need to take a vitamin D supplement. Because sun exposure in that region is insufficient for several months of the year, living at high latitudes can impact one’s vitamin D status.

Dark-skinned people, the elderly, those who cover their bodies excessively with clothing for cultural reasons, and those who frequently use sunscreen are all at risk of vitamin D insufficiency. Another point of worry for vegans is that vitamin D2, the vegan-friendly version of vitamin D, is significantly less accessible than animal-derived vitamin D3.

In the winter in Finland, vegans’ vitamin D consumption was insufficient to keep serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone concentrations within normal ranges, which appeared to have a deleterious impact on long-term BMD. Vegan women had lower serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and higher parathyroid hormone levels throughout the year than omnivores and other vegetarians. Vegans have a 12 percent lower BMD in the lumbar area of the spine than omnivores.

Iron

The absorption of heme iron from plant meals is significantly higher than that of non-heme iron. However, when comparing vegans to omnivores and other vegetarians, hemoglobin concentrations and the risk of iron deficiency anemia are equal. Vegans frequently consume substantial amounts of vitamin C–rich foods, which significantly boost nonheme iron absorption.

Some vegans have lower serum ferritin concentrations, but the average values are similar to those of other vegetarians but lower than those of omnivores. At this time, the physiologic implications of low serum ferritin concentrations are unknown.

Vitamin B-12

Vegans have lower plasma vitamin B-12 concentrations, a higher frequency of vitamin B-12 deficiency, and higher plasma homocysteine concentrations than lactoovovegetarians and omnivores. Homocysteine elevation has been linked to cardiovascular disease and osteoporotic bone fractures.

Ataxia, psychoses, paresthesia, disorientation, dementia, mood, and motor abnormalities, and difficulties concentrating are some of the atypical neurologic and mental signs of vitamin B-12 insufficiency. Apathy and failure to thrive are also common in youngsters, and macrocytic anemia affects people of all ages.

Zinc

Zinc deficiency is commonly thought to be a problem for vegetarians. Phytates, which are found in grains, seeds, and legumes, bind zinc, reducing its bioavailability. However, a sensitive marker for determining zinc status in humans has yet to be discovered, and the effects of minor zinc intakes remain unknown.

Vegans have a lower zinc consumption than omnivores, but their functional immunocompetence, as measured by natural killer cell cytotoxic activity, is comparable to nonvegetarians. There appear to be zinc absorption facilitators and compensatory mechanisms to assist vegetarians in adjusting to a lower zinc intake.

DIETARY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OPTIMAL VEGAN DIETS

1) Vegans should consume vitamin B-12–fortified foods, such as fortified soy and rice beverages, certain morning cereals and meat analogs, and B-12–enriched nutritional yeast, regularly to avoid B-12 deficiency, or take a daily vitamin B-12 supplement. Active vitamin B-12 cannot be found in fermented soy products, green vegetables, or seaweed. There are no large amounts of active vitamin B-12 in unfortified plant foods.

2) To maintain adequate calcium in the vegan diet, calcium-fortified plant foods should be consumed regularly in addition to traditional calcium sources (green leafy vegetables, tofu, tahini). Ready-to-eat cereals, calcium-fortified soy, and rice beverages, calcium-fortified orange and apple juices, and other beverages are among the calcium-fortified foods.

Calcium carbonate in soy beverages and calcium citrate malate in apple or orange juice have bioavailability similar to that of calcium in milk. The calcium bioavailability of tricalcium phosphate–fortified soy milk was found to be somewhat lower than that of cow milk.

3) Vegans must take vitamin D–fortified foods such as soy milk, rice milk, orange juice, breakfast cereals, and margarine regularly to maintain adequate vitamin D levels, especially during the winter. In the absence of fortified foods, a daily dosage of 5–10 g of vitamin D would be required. Vegans over the age of 60 would benefit greatly from the vitamin.

4) Plant items naturally rich in the n-3 fatty acid ALA, such as ground flaxseed, walnuts, canola oil, soy products, and hemp seed-based beverages, should be consumed regularly by vegans. Vegans should also take items supplemented with the long-chain n-3 fatty acid DHA, such as soy milk and cereal bars. DHA-rich microalgae supplements would assist those with higher long-chain n-3 fatty acid requirements, such as pregnant and breastfeeding women.

5) Due to the high phytate content in a normal vegan diet, it is critical for vegans to consume zinc-rich foods such as whole grains, legumes, and soy products to ensure adequate zinc consumption. Vegans who consume fortified ready-to-eat cereals and other zinc-enriched foods may also benefit.

SUMMARY

Vegans are slimmer, have lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels, and have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease. When calcium and vitamin D consumption is inadequate, BMD and the risk of bone fracture may be a problem. Calcium- and vitamin D-fortified foods should be consumed regularly if they are available.

More research into the link between vegan diets and the risk of cancer, diabetes, and osteoporosis is needed. Vegans are at risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency, making the usage of vitamin B-12–— -fortified meals or supplements vital. Vegans should take meals high in ALA, DHA-fortified foods, or DHA supplements regularly to improve their n-3 fatty acid status.

Vegans consume a healthy amount of iron and do not suffer from anemia at a higher rate than the general population. Vegans can usually avoid nutritional difficulties if they eat the right foods. Their health looks to be on par with that of other vegetarians like lactoovovegetarians. (References 83–109 are found in other papers in this Journal supplement.)